In my previous post, I presented new data on the aggregate effective tax rates of US companies by jurisdiction. What I showed is that the aggregate foreign effective tax rate of US companies in the Compustat database has declined sharply, from 42 percent in the mid- to late-1980s, to 26 percent today. The aggregate federal effective tax rate paid by those same companies has remained more or less the same.

This pattern, I suggested, is indicative of a long-term global convergence, with foreign tax rates catching up to the low rate regime of the US. This evidence brings into question the Trump administration’s rhetoric, which suggests that the US federal tax system severely hampers the global competitiveness of US companies. And Trump’s corporate tax reform agenda could have serious ramifications for the global political economy. Any effort to significantly reduce the federal corporate tax rate could lead to a global downward spiral: another process of convergence at even lower rates across the world in the future.

The data presented in my previous post are “aggregate” in two senses. First, due to the extreme year-to-year volatility in company-level tax rates, I aggregated the data across several years. Put simply, I took the total sum of income taxes for all Compustat companies across several years and divided them by the total sum of pre-tax income for those years to develop various aggregate effective tax rates. Second, the measures I developed were aggregated in the sense that they were focused on all companies in the Compustat database. I made no effort to disaggregate the Compustat sample by sector, size, or some other characteristic.

In this post, I retain the first technique of aggregation in relation to tax rates, but go beyond the second meaning of aggregate to compare tax rates based on firm size. Specifically, I examine the aggregate federal and foreign effective tax rates for the top 50 companies ranked by revenues versus “the rest” of the companies in the Compustat database. One more cautionary note about the limitations of Compustat needs to be stated before proceeding. As I mentioned in the previous post, the total number of companies reporting these particular items is quite small, ranging from around 880 in 1994 to 2,000 in more recent years. Thus the category of “the rest” does not include all US companies outside of the top 50.

Yet one of the advantages of using Compustat is that it includes a wide of range of companies. For example, “the rest” for 2015 includes large corporations such as Blackrock (with assets of $225 billion), all the way down to lesser known entities like Blackcraft Cult Inc, a purveyor of goth and metal clothing (with assets of $637,000). Thus my categories of top 50 and “the rest” do not just compare the gargantuan and the big. “The rest” is a hodgepodge of small, medium, and large companies that we can compare to the top 50, which represent the giants at the very apex of the business hierarchy.

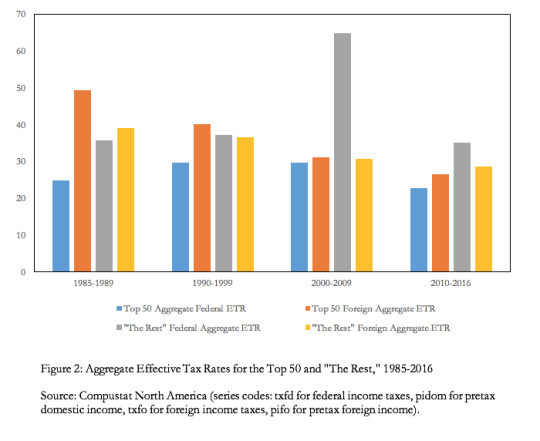

Figure 2 shows the aggregate federal and aggregate foreign effective tax rates (ETR) for the top 50 and the rest from 1985-1989 to 2010-2016. Something that jumps out immediately in the figure is the tall grey bar for 2000-2009, standing like 432 Park Avenue over the midtown skyline. The massive jump in the aggregate federal ETR for “the rest” during this period is due to the collapse of pre-tax domestic income in 2001 and 2008. “The rest” incurred heavy losses with the dot com collapse and the global financial crisis, and the pre-tax domestic income of the entire sample actually turned negative during these years.

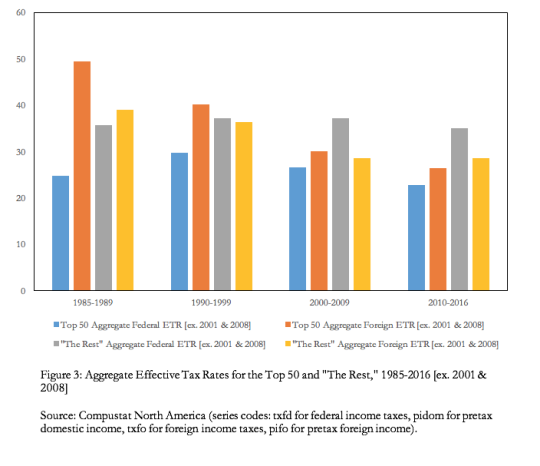

Now, it might be tempting to dismiss the findings for 2000-2009 as exaggerated due to the distorting effects of the crises. So I play it safe. Figure 3 replicates Figure 2, but removes data for 2001 and 2008 from all four measures of the tax rate.

As we see, for the top 50, the aggregate federal ETR shows no clear pattern. The rate moves slightly up and down from period to period, and ranges from a high of 30 percent in 1990-1999 to a low of 23 percent in 2010-2016. The aggregate foreign ETR of the top 50 steadily declines from 49 percent in 1985-1989 to 26 percent in 2010-2016. In every period the aggregate federal ETR of the top 50 is lower than its aggregate foreign ETR. As such, the US federal tax system does not appear to hamper the global competitiveness of the largest US corporations.

As we also see in Figure 3, the aggregate federal ETR of “the rest” stays remarkably consistent, hovering at around 35 percent. Meanwhile, the aggregate foreign ETR of “the rest” declines slightly from first period to the second period, then stabilizes at 29 percent in latter two periods. Apart from earliest period (1985-1989), the aggregate federal ETR of “the rest” is higher than its aggregate foreign ETR. Thus the US federal tax system does appear as a drag on the global competitiveness of all but the largest US companies.

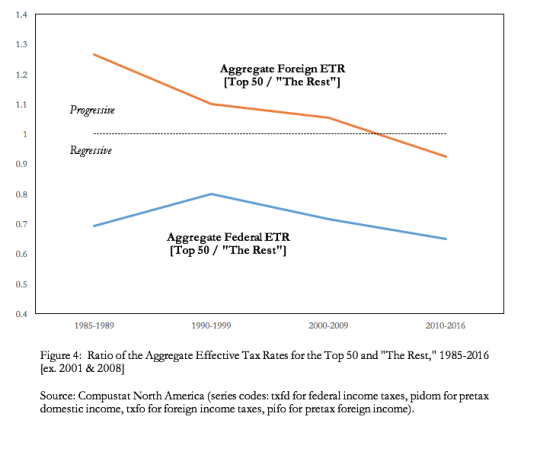

Figure 4 brings the comparison of the top 50 and “the rest” into sharper relief. The figure shows the ratio of the aggregate federal and aggregate foreign ETRs of the top 50 relative to “the rest.” The ratios can be interpreted as measures of the progressivity of the federal and foreign tax regimes. A ratio above one indicates a progressive tax regime (i.e. large corporations are subject to a higher rate than “the rest”), a ratio below one indicates a regressive tax regime (i.e. large corporations are subject to a lower rate than “the rest”).

The top line in Figure 4 shows the ratio of the aggregate foreign ETR of the top 50 relative to “the rest.” What we see is a steady decline in the progressivity of the foreign regime. The top 50 were subject to a much higher foreign rate in 1985-1989, but the gap has been narrowing ever since. For the latest period (2010-2016) the ratio falls below one for the first time, indicating that “the rest” are now subject to a foreign rate than is higher than the very largest US companies.

The bottom line in Figure 4 shows the ratio of the aggregate federal ETR of the top 50 relative to “the rest.” Here we see that the federal tax system has been consistently regressive since the mid- to late-1980s, and the ratio falls to its lowest level in the most recent period (0.65). In other words, the top 50 have been subject to lower federal tax rates relative to “the rest” over the long-haul.

What does it all mean?

Figure 1 in my previous post highlighted the fact that, although the tax rate on foreign income has been falling, US companies are subject to a lower rate on their domestic income. The findings suggest that foreign regimes have been catching up to the low rate regime of the US. These empirical facts fly in the face of the Trump administration’s (post-factual) rhetoric, which claims that the US federal tax regime hampers the global competitiveness of US companies.

Digging deeper and disaggregating US companies by size provides a whole new perspective on the corporate tax debate. The top 50 US companies have seen their aggregate foreign ETR steadily decline since the mid- to late-1980s, but their aggregate federal ETR has been consistently lower in every period for which data is available. When looking specifically at the very largest US companies, the case for lowering the corporate tax rate in the name of global competitiveness is further weakened.

Yet when we look look at it from the perspective of “the rest” of the companies outside of the top 50, the story changes completely. The foreign aggregate ETR of “the rest” has declined slightly over time, but its federal aggregate ETR has held consistent at around 35 percent (which just happens to be the top statutory federal rate). Since the 1990s, “the rest” has been subject to a federal tax rate that is higher than its foreign rate. What is more, the top 50 is now subject to lower federal and foreign rates relative to “the rest.”

In the aggregate (meaning all of the companies reporting jurisdictional tax data in Compustat), there is little justification for the Trump administration’s calls for lowering the statutory federal tax rate in the name of global competitiveness. But in the disaggregate, there certainly is some justification for tax reform, insofar as it aims at leveling the competitive playing field in favour of “the rest.”

Unfortunately, though, this type of disaggregate perspective rarely enters into the public debate. Even the warring factions within the current administration, the economic nationalists versus the so-called ‘globalists,’ operate under the assumption of a unified national interest. They only differ on the question of whether that unified national interest is threatened by cooperation with the rest of the world, especially with China.

It will be up to progressive voices to ensure that issues of domestic power and inequality enter into the current debates.