The first nine months of the Trump presidency have been rough. After failing to repeal Obamacare, the administration has now shifted its sights toward comprehensive tax reform. One of the centrepieces of the tax plan is to reduce the statutory federal corporate tax rate from the current 35 percent to anywhere between 15 to 25 percent. The line from the administration justifying the corporate tax cut is simple enough: the US statutory corporate tax rate is one of the highest in the OECD, and without a significant reduction, US companies will be unable to compete in the global economy. A significant reduction in the tax burden, so the argument goes, will free up money for US corporations to invest and create jobs at home.

But Trump’s rhetoric on corporate taxation (as with pretty much everything else) grossly over-simplifies a more complex reality. The over-simplification starts with the president’s fixation with the statutory tax rate. What matters to companies isn’t the statutory (official) rate per se, but the effective rate — the actual amount of taxes that a company pays as a percentage of its total income. Thanks to loopholes, tax credits, and other means, companies are often able to reduce their effective tax rate well below the statutory rate declared by law. The discrepancy is borne out by the data: in recent years, studies have shown that the effective tax rate of large US companies has been significantly lower than the statutory rate.

The fact that effective rates are lower than statutory rates, however, tells us little about the global competitiveness of US companies. In order to assess Trump’s claim that US companies face a disadvantage we need to compare their effective tax rates to the effective tax rates of relevant competitors in other parts of the world. Examining the 100 largest US corporations to the largest 100 European corporations from 2001 to 2010, Reuven Avi-Yonah and Yaron Lahav found that the Europeans faced higher effective tax rates in eight of the ten years. For the entire period, the effective tax rate of large US corporations was 31 percent, and 35 percent for large European corporations.

Yet even this important study has its limitations. The data compiled by Avi-Yonah and Lahav are based on worldwide tax rates — the amount of total worldwide taxes companies pay divided by the their total pre-tax income. Though these data are appropriate for assessing the global competitiveness of large US corporations, they do not allow us to address the main issue raised by the Trump administration: the role that the US federal tax policy plays in helping or hindering the global competitiveness of US corporations.

To address this issue, we would have to examine not only the worldwide effective tax rate of US companies relative to foreign competitors, but would also have to breakdown the effective tax rates that US companies pay by jurisdiction. In other words, we would have to examine the effective tax rate that US companies pay on their domestic earnings relative to the effective tax rate they pay on their earnings abroad. To my knowledge, no one has actually offered a study of this type, and in the remainder of this post I am going to outline some of the early (and tentative) fruits of my own research in this area.

One source offering detailed breakdowns of corporate taxes by jurisdiction is Compustat, an extensive database that includes company financial statements. As far as corporate taxes are concerned, Compustat has three main data items: total income taxes (which include deferred charges), current income taxes (which represent the total tax liability of the company according to the tax code), and income taxes paid (which represent the actual cash taxes a company pays to tax authorities). The second item, current income taxes, can be further broken down into three categories based on jurisdiction: federal income taxes, state income taxes, and foreign income taxes. Compustat also has data on pretax income, which can be further broken down into pretax domestic income and pretax foreign income. This means that Compustat can be used to develop effective tax rates by jurisdiction: we can calculate the federal effective tax rate (federal income taxes as a percentage of pretax domestic income), and the foreign effective tax rate (foreign taxes as a percentage of pretax foreign income).

Anyone who has ever worked with company-level tax data knows the frustrations in trying to develop historical measures. For individual companies, the effective tax rate can swing wildly from year-to-year, and during major crises, many companies report negative pretax income, which makes the tax rate impossible to interpret (on the surface of things, a negative tax rate may seem like a good thing for a company, but not if it is the product of a negative denominator and a positive numerator).

One way around these problems is to follow a technique developed by Avi-Yonah and Lahav and calculate the aggregate effective tax rate (see also Dyreng et al 2008). Instead of calculating the effective tax rate for each individual company and then averaging those individual rates, an aggregate tax rate sums together all companies’ income taxes during a certain time period and divides them by all companies’ pre-tax income during that same period. To smooth out the business cycle, we can sum together the data in the numerator and the denominator over three, five, or even ten year periods.

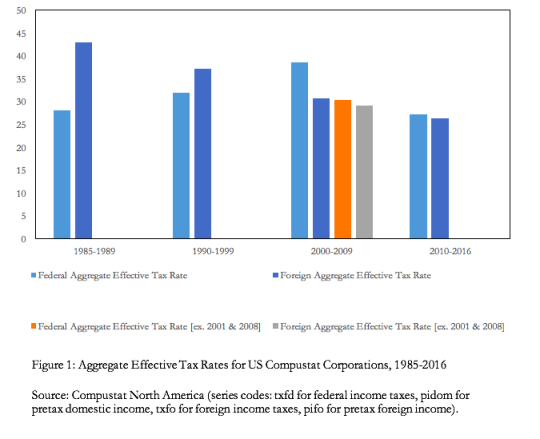

Figure 1 shows the aggregate federal and the aggregate foreign effective tax rates for all US corporations in the Compustat database that report these data items. Specifically, the figure shows the aggregate sum of federal and foreign taxes for a specific period divided by the aggregate sum of domestic and foreign pre-tax income for that same period. The periods are divided by decades, except in the case of 1985-1989 (where earlier data are unavailable) and 2010-2016.

Now, before analysing the figure, it is worth briefly mentioning some of the limitations of the Compustat data. The total number of companies reporting these particular items is quite small, ranging from around 880 in 1994 to 2,000 in more recent years. Commercial banks are not included in the sample, as they are not required to report a breakdown of taxes and pre-tax income by jurisdiction. Finally, although Compustat coverage stretches back to 1950, the data for these particular items, as hinted at earlier, only go back to 1985.

What does Figure 1 tell us? Let’s start with the earliest period. During 1985-1989 we see that the aggregate federal effective tax rate of 28 percent for US companies was much lower than the aggregate foreign effective tax rate of 42 percent. Since then, the aggregate foreign effective tax rate of US companies has steadily declined, and stands at 26 percent for the most recent period from 2010-2016. Even when we remove the crisis years of 2001 and 2008, the decline in the foreign rate remains. The pattern of aggregate federal effective taxation is harder to discern. The federal rate moves up and down over time and appears to be heavily influenced by the business cycle, rising and then falling in the most recent period. But when we remove the crisis years of 2001 and 2008, during which pretax domestic income collapsed, the discrepancy between the foreign and effective rates during the 2000-2009 period disappears.

The data in Figure 1 suggest that there has been a long-term global convergence in corporate tax rates. Today the tax rate that US companies pay on their domestic and foreign income is almost identical at 27 and 26 percent, respectively. US federal tax policy does not, as the Trump administration would have us believe, hamper the competitiveness of US corporations. If anything, the data in Figure 1 show that the rest of the world has been engaged in a decades-long process of catching up to the US’s low corporate tax regime. Significant cuts to the corporate tax rate in the US now could engender a downward spiral, leading to another process of convergence at even lower rates across the world in the future.

Thus far, the debate over corporate tax reform has been focused almost exclusively on the national level: does federal tax policy help or hinder the competitiveness of US companies abroad? But with whose competitiveness are we ultimately concerned? Given the resurgence of interest in the market power of large firms in recent years, it is worthwhile to disaggregate the corporate sector and examine the jurisdictional tax rates of large US firms versus other US firms. How do the aggregate federal and foreign effective tax rates of large firms compare to ‘the rest’? And how have they evolved over time?

These are the questions that I will tackle in my next post. As a teaser: this is where the story gets very interesting.