Back in September I took part in a panel discussion with Anastasia Nesvetailova and Alexander Lanoszka entitled “Brexit, Trump, and Other Madness: The New Politics of Inequality.” Below, I’ve posted an edited and abridged version of my comments.

INTRODUCTION

How do we explain Trump’s popularity?

As many people have suggested, an important part of the answer to this question has to do with growing wealth and income inequality in America. But what I’m going to suggest to you today is that inequality, although central, can only get us so far in accounting for Trump’s rise.

After all, there’s no universal law of history that says that rising inequality automatically leads to the racist, misogynistic, xenophobic, brand of right wing populism that Trump represents. In response to growing inequality, we also get more inclusive, progressive forms of populism like the one offered by Bernie Sanders.

And so what I want to do is outline the connection between Trump and inequality. And then I want to briefly discuss two other key factors that help to explain this phenomenon of Trumpism. These other two factors are ideology and working class organization.

INEQUALITY

Let’s start with the connection between Trump and inequality.

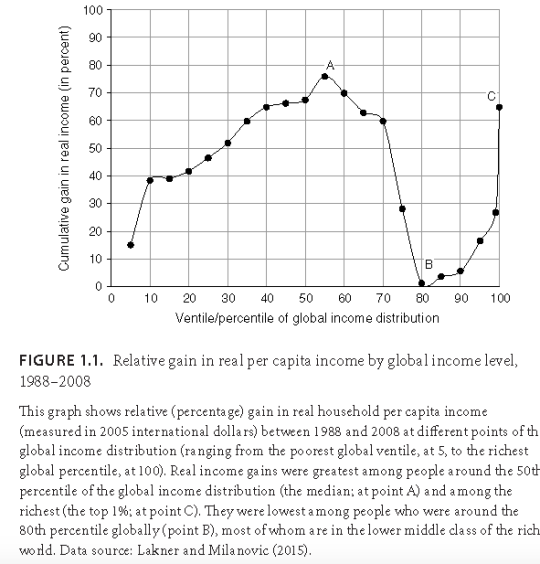

I’m sure many of you have seen this chart (Figure 1.1), which has been making the rounds on social media. It comes from Branko Milanovic’s wonderful new book Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization. And this chart has become known as the “elephant chart” because the shape of its series bears a striking resemblance to the head of an elephant.

What the chart does is show the relative gains in “real” per capita income from 1988 to 2008 based on where people find themselves in the global distribution of income.

At point C we find the global top 1%. These are the global elite at the top of the wealth and income hierarchy. And what you see is that they’ve done very well in the age of globalization; their incomes have seen an increase of almost 70 percent over this period.

At point A, the head of the elephant, we find another group that’s done very well. These are people in roughly the 40th to 70th percentile of global income distribution. And these are primarily the new middle classes in emerging markets such as China. This group has also seen its increase grow by 60 to 70 percent in the age of globalization.

And finally, we have point B, or those people in the 80th to 90th percentile of global income distribution. Within this group you find the lower and middle classes in advanced capitalist countries. And here you see that in relative terms, these people have been the real losers of globalization. These are the people that have lost highly paid manufacturing jobs and that have seen their incomes stagnate over the past couple of decades. It is people within this category (point B) that have provided most of the support for Trump. As the primary losers of globalization, these people find Trump’s rhetoric on trade protectionism and immigration particularly appealing.

So in this sense, there is a clear relationship between the rise of Trump’s populist movement and inequality. But then we are left with the question of why some people gravitate toward Trump’s particular brand of populism and not the progressive populism of someone like Bernie Sanders. Inequality might be necessary to explain Trump’s rise, but it’s not sufficient to explain why some working class Americans flock to Trump instead of Sanders.

Sanders might not be as tough on immigration, but he just as tough on trade. And unlike Trump, Sanders actually addresses issues of inequality and redistribution in his speeches and policy proposals.

So why do some working class Americans choose Trump over Sanders? This is obviously a complicated question, on that could fill an entire PhD thesis. And I’m not going to pretend that I have a complete answer. Instead, I’m going to propose two addition factors that I think our important to explain the linkage between Trump and inequality. The first factor is ideology and the second factor has to do with working class organization.

IDEOLOGY

I think that part of Trump’s appeal has to do with ideological traits that are somewhat unique to the United States. And these ideological traits are captured in a brilliant quote from the famous American novelist John Steinbeck. When was to explain why the US has never had a meaningful socialist movement, Steinbeck responded with the following:

Socialism never took root in America because the poor there see themselves not as an exploited proletariat but as temporarily embarrassed millionaires.

In the land of the free and the land of the free and the land of opportunity, there is an entrenched belief in social mobility. And unlike in Western Europe, class just isn’t a category through which most Americans understand their society. Some elements of the working class can relate to Trump, and they can relate to him in part because they believe in the possibility that they might become like him some day.

There’s also a certain reverence for the businessman in American culture. And Trump’s supporters truly believe that Trump accumulated his fortune through hard work, intelligence, and thriftiness. And there’s a hope that Trump is going to use this supposed business acumen to steer the economy in the right direction. Trump the “job creator” providing wealth and prosperity for all.

WORKING CLASS ORGANIZATION

Another factor that helps to account for Trump’s popularity has to do with working class organization. This is something that was first reported in the New York Times back in August. And I think that focusing on working class organization gives us a compelling explanation for why white working class men in particular have thrown their support behind Trump and his right wing brand of populism.

When we think of trade unions, we tend to think of organizations that exist in order to bargain for higher wages and better working conditions. But research cited in this New York Times article has shown that unions play a much broader political role. And in particular, unions play an important role in socializing the working class into progressive values.

Research has shown that in 2008 unionized whites tended to vote for Obama, while non-unionized whites voted for McCain. There’s also a study showing that unionized workers in Western Europe are less likely to support far-right political parties than their non-unionized counterparts.

Now, unions in the United States have also led the charge against Trump during the current election campaign. But the problem is that unions are fighting a losing battle because of their declining influence.

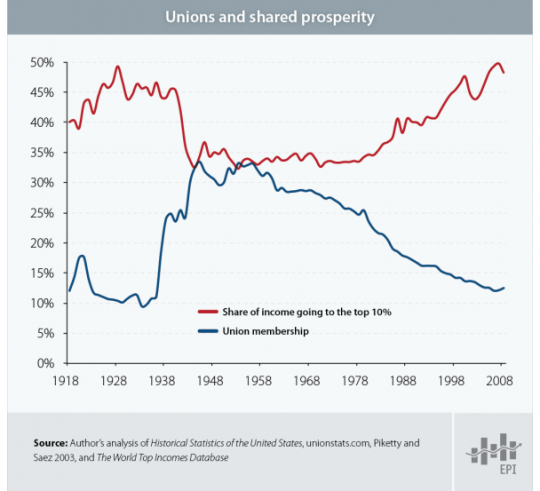

This next chart is from the Economic Policy Institution. The blue line in this chart shows the percentage of the adult population in the United States that belongs to unions. What you see is that the rate of unionization in the US has been plummeting since the 1960s, and now it’s almost as low as it was in the 1920s and 1930s.

CONNECTING THE DOTS?

The red series in the above chart shows the income share of the infamous top 1% in America. And so there’s a clear correlation here: as unionization has declined, the income share of the top percentile has greatly increased.

I’m not going to try to pick apart the causal relationship, but I do think that what we have here is a sort of vicious circle. First, we have increasing income inequality, which tends to breed populism. Second, we have declining union membership, which tends to breed right wing populism over more progressive alternatives. And finally, we have this mythical, almost cult-like, reverence for a sociopathic billionaire, who still has a chance of becoming the next president of the United States.

Even a year ago, I don’t think many people saw this coming. But given how desperate the situation is for many in America, I don’t think we should be so shocked about the fact that Trump has managed to make it this far.