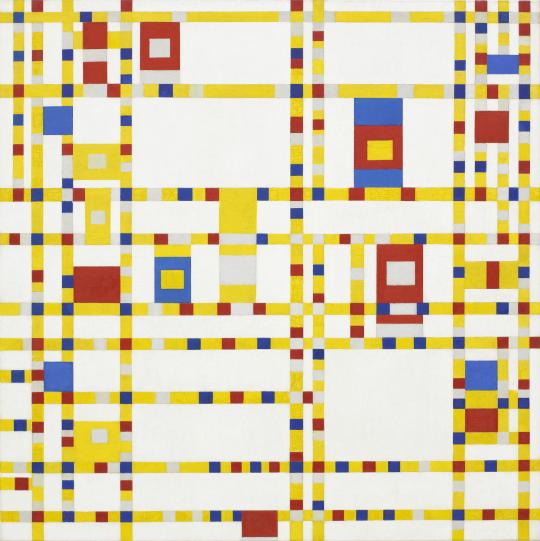

“Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1942-43) – Piet Mondrian

Book 1 of My Struggle, Karl-Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume autobiography, is about life, the complications of life, and the thing that complicates our lives above all else: our relationships, especially with our families. Relationships become most complicated in the context of life’s opposite — death — which Knausgaard proclaims, paradoxically, to be “the greatest dimension of life”.

One way to try to make sense of life (and death) is through art. And Book 1 of My Struggle contains several reflections on art, which are, to my mind, full of insight. There is something within art, particularly within painting, that speaks to our experiences, yet transcends those experiences at the same time. Art is us and beyond us. There is something inexhaustible about art; it is a space between reality and the portrayal of reality. In Book 1 of My Struggle Knausgaard twice mentions Rembrandt’s self portrait as an old man, a painting that hangs in the National Gallery in London. Amid the candid portrayal of bodily decay, Rembrandt manages to capture the light in his own eyes, the one feature of the human body that is to impermeable to the destructive process of aging. Peering into Rembrandt’s eyes gets us as close as possible to another human soul.

As Knausgaard explains, this feeling that art evokes is not something that can be easily be explained or analyzed, no matter how much we know about art and art history. The feeling of art is not dependent on a particular epoch or style or painter. Nor is feeling a matter of quality, technique, talent or fame. A Finnish impressionist, unknown outside of Finland, fills Knausgaard with a sense of warmth while Monet leaves him unmoved. But if there is one characteristic that unifies the art that moves him it is that all of it was created before 1900. Pre-twentieth century art, for all its diversity, has a “great beyond” (that space between reality and the portrayal of reality) that serves as the source of emotion for Knausgaard. Until the Enlightenment, the great beyond was the divined expressed to us through Revelation. For romanticism, the great beyond was nature, expressed through the sublime.

Yet Knausgaard argues modern art has gotten rid of the great beyond. Man used to be subordinated to the divine and to the natural landscape, but ever since Munch, man has been at the centre. Art has closed itself in on humanity and thus rid itself of anything outside of that human world. And without a great beyond, modern art leaves Knausgaard feeling cold.

The last remaining great beyond for humanity is, in fact, death. But since we no longer acknowledge a great beyond, Knausgaard points out how modern society treats death in a strange way. Death is ubiquitous: we hear news of death, see pictures of dead people (real or fake). But this is death as an idea, death as a concept; it is death without a dead body. Just as modern society fixates on death as an idea, it tries very hard to hide the physical aspects of death, “with such great care that it borders on a frenzy”. This strange way of dealing with death manifests itself in the accounts of people who have witnessed a murder or a car crash: they describe it as “absolutely unreal”.

I find it easy to accept at least some of Knausgaard’s cynicism toward modern art. Given some of my own experiences with contemporary art exhibits, I cannot help but grin when reading his dismissal of what art has become: “an unmade bed, a couple of photocopiers in a room, a motorbike in an attic”. And yet I wonder whether I truly share Knausgaard’s sweeping sentiments about the inability of modern art to evoke any feeling whatsoever. At the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an encounter earlier this year with Piet Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie compelled me to think more carefully about my own experiences with modern art in light of Knausgaard.

Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) was one of the many European artists and intellectuals to seek refuge in New York during World War II. He was a member of a movement known as De Stijl — an abstract style stripped down to the essentials of form and colour. In The Story of Art, E.H. Gombrich explains how Mondrian “wanted to build up his pictures out of the simplest elements: straight lines and pure colours. He longed for an art of clarity and discipline that somehow reflected the objective laws of the universe”.

Straight lines, pure colours, clarity and discipline. These are certainly the things that stand out in Broadway Boogie Woogie. This painting might not seem like a good candidate for uncovering feeling in modern art. In fact De Stijl — in trying to pin down universal laws in abstracted geometric forms — probably embodies the spirit of contemporary art of which Knausgaard finds so impoverished. And yet, my own personal experience with this painting was, for lack of a better word, memorable.

On a busy Saturday afternoon, I was left alone with this painting in a corner of the fifth floor, tucked away from the crowds that were gathered around Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans and Matisse’s Dance (I). I have to admit that Mondrian’s painting (for some reason I have a hard time referring to it by its ridiculously kitschy name “Broadway Boogie Woogie”) did not bring me to tears. But it did fill me with a sense of joy, of warmth, and of energy. Perhaps the feeling isn’t as strong as that evoked by Rembrandt’s self-portrait, and it certainly did not give me a window into the divine or the sublime. But there was nonetheless something about this painting that moved me, and something that moved me quite fundamentally for days after. It kept coming back to me at odd times, once when I was cleaning the kitchen or grocery shopping.

So what is it about this painting with a kitschy name in particular, this rather odd, seemingly emotionless painting, that left such an impression? Let’s start with what the painting is about. As the MoMA description makes clear, this painting reflects Mondrian’s impressions of New York, both its architecture and its music scene. In it, we see the cartography of Manhattan’s grid system and bright lights, which must’ve boggled the mind of someone accustomed to the medieval meanderings of Dutch cities and villages. Following the pattern of lines and squares is akin to following the intricate time signatures of a jazz riff.

There is something in Mondrian’s painting that captures a paradox of ordered randomness. I think it is this spellbinding combination of the complex and the random that has left a lasting impression. It’s also what makes life in the modern metropolis so alluring. Everyday I find myself in awe of big cities and how they manage function at all. How can megacities even exist with all the chaos of diverse humanity that flows through them?

There’s something mysterious if not magical, perhaps even something inexhaustible, that explains it. Of course there are plenty of negative things that ensure that megacities work: advertising to shape human wants, control and discipline administered by the job market and the state. But there’s also something positive, a sort of spirit at work as well. In New York, I think social order is maintained in large part due to exuberant friendliness (despite the common perception of New York as unfriendly, I consider it to be one of the friendliest major cities in the Western world). In London, humour and manners play an important role.

We create the urban environment, but this environment takes on a life of its own. There’s something mysterious in this — if not a ‘great beyond’, it is still something beyond humanity. That something lies at the intersection of order and randomness, which is captured by Mondrian’s painting. For me, this is a source of emotion. The feeling might not be as strong as the divine, but it is enough, at least for me, to appreciate some of the great works of modern art on their own terms.