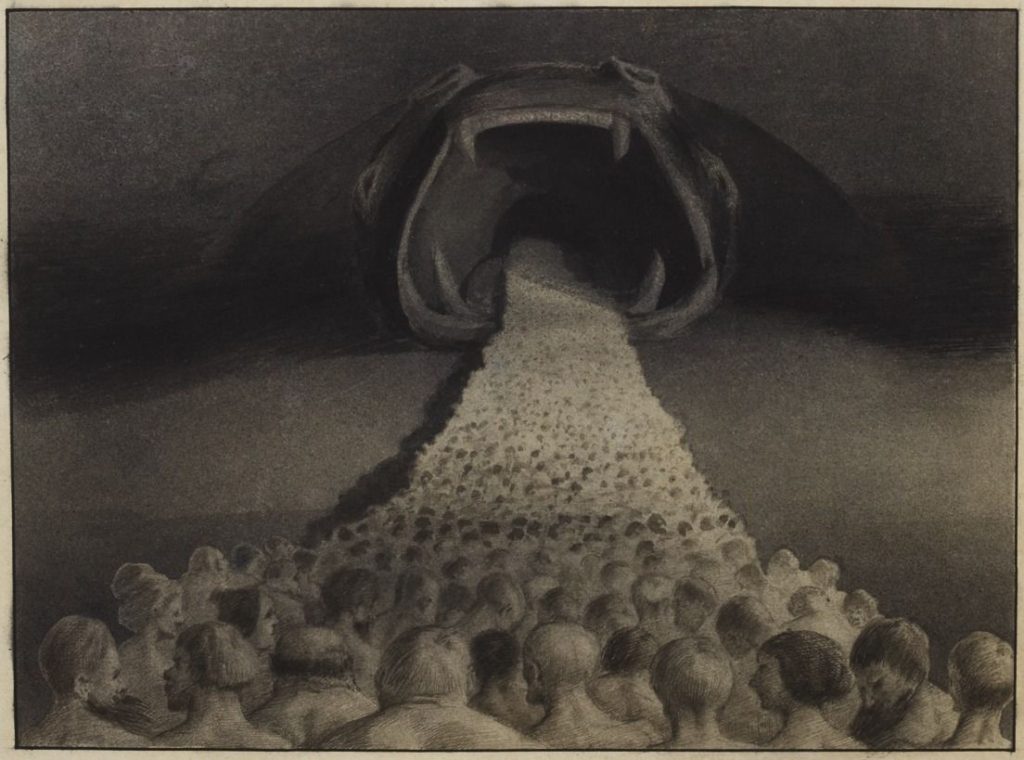

‘Into the Unknown’ (1900) – Alfred Kubin

A summer ritual of mine over the past few years has been to read my way through Karl Over Knausgaard’s colossal six-volume autobiographical novel My Struggle. Deftly described in a New York Times review as a 3,600 page Norwegian novel about a man writing a 3,600 page Norwegian novel, I devoured the first five volumes, finishing each of them in just a few days . There’s something about the way that Knausgaard writes, the almost mesmerising detail interwoven with profound yet clearly-articulated insights, that made the journey through the first five volumes seem almost effortless. A rare talent it is for someone to be able to write at length and in great detail about the seemingly mundane — cleaning a house or hiding beer outdoors in winter — and make it not only engaging, but also beautiful, and, at times, even suspenseful. This past summer I managed to complete the final volume, and it was, by some measure, my least favourite. The effortlessness of the previous five volumes gave way, for lack of a better term, to a personal struggle with My Struggle.

At 1,153 pages, the sixth volume is the longest of bunch. It is divided into three parts. Part One takes place just as the first volume of My Struggle is about to be published and recounts the controversies generated by the novel as intimate details of the lives of family and friends become public. One of the main ideas explored here concerns the reliability of our memory. Why does our recollection of the distant and not-so-distant past often clash with the recollection of others? Who has a legitimate claim to truth when this happens? And if someone contests another’s portrayal of past events does that person have the right to prevent that portrayal from entering the public domain? In Part Three, Knausgaard considers the consequences of his rise to fame as subsequent volumes are published, focusing on the strain this puts on his relationship with his wife Linda.

Sandwiched in between is Part Two, the largest section. These 455 pages, entitled “The Name and the Number,” begin in familiar territory, with Knausgaard debating whether or not to use his father’s real name in the book. But the discussion soon deviates from autobiography and in place of a Norwegian novelist writing-about-writing a Norwegian novel, we get an essay, a meandering cultural analysis of the twentieth century. Through an exploration of Celan, Kubin, Shakespeare, Faulkner, Kafka, Hamsun, Joyce, the Old Testament, Zweig, and Hitler, Knausgaard is trying to get at the dangers of referring to people as numbers instead of by name. This sweeping account underscores the centrality of language, and in particular, the centrality of the pronouns I-you-we-they-it, in connecting the personal with the social.

On its own, “The Name and the Number” might stand as a brilliant and insightful essay. But I found myself disengaged, and at times even irritated, with this part of the book. Why irritation? The trouble, as I see it, is that this essay simply doesn’t fit with the other 3,000 plus pages of My Struggle. The rest of the novel is a deeply personal, painfully candid, meticulously detailed, account of one man’s life. This individual, Karl-Ove Knausgaard, is not politically active, and never espouses any firm political views. Knausgaard is certainly not a person at the centre of defining moments in history, and to his credit, never claims to be. The I-you-we-they-it Knausgaard engages is a narrow one; it rarely extends beyond a close group of family members and friends. Before his rise to fame he lives out a normal life in tranquil (sometimes sedate) settings in rural Norway, Stockholm, and Malmö.

In this way, My Struggle is the antithesis of Stefan Zweig’s autobiography The World of Yesterday. This panoramic view of Zweig’s life in bourgeois Vienna unfolds from his childhood (which he refers to as the ‘age of security’) through World War I and the interwar period (including the years of hyperinflation), and ends with the outbreak of World War II. Zweig was a person who, unlike Knausgaard, is swept up in some of the defining moments of history. The I-you-we-they-it Zweig engages is much broader, including key political figures, as well as the important members of Vienna’s artistic and intellectual scene. What is most striking about Zweig’s autobiography is the almost complete lack of references to his personal life. Whereas Knausgaard gives us intimate portraits of all of his close family members, Zweig mentions only in passing his parents, his brother, his children, and his wives.

Perhaps there’s a trade-off in autobiography: it can either be deeply personal or more broadly social-political-historical. In any case, Knausgaard’s attempt to do both in the final volume of My Struggle feels artificial.