This piece was written for In the Long Run.

Near the tail end of a tumultuous first year in office, Donald Trump scored a major legislative victory, as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was signed into law. One of the major changes introduced by the bill is a reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent. The administration’s justification for this was straightforward: the US statutory corporate tax rate was one of the highest in the OECD, and this was seen as a fetter on the competitiveness of US companies in the global economy. A significant reduction in the tax burden, it followed, would free up money for these companies to invest and create jobs at home.

As with most other issues, Trump’s rhetoric on corporate taxation grossly over-simplifies what is, in fact, a complex reality. The over-simplification starts with the president’s fixation on the statutory corporate tax rate. When it comes to the question of global competitiveness, what matters isn’t the statutory rate per se, but the effective rate – the actual amount of taxes companies pay as a percentage of their total income. Due to loopholes, tax credits and other accounting wizardry, companies are often able to reduce their effective tax rate well below the statutory rate officially declared by law. A focus on effective rather than statutory corporate tax rates leads to a very different assessment of the relationship between the US federal tax system and global competition.

In what follows, I break down the effective tax rates of US companies by jurisdiction – examining the rate they pay on their domestic and foreign earnings. What I find is that there has been a long-term convergence between the federal and foreign effective tax rates paid by US corporations. Rather than the federal tax system hampering the competitiveness of US corporations, the rest of the world has instead been engaged in a decades-long process of convergence toward the US’s low-rate corporate tax regime. These empirical realities should make us question the Trump administration’s rationale for corporate tax reform.

The research here is based on the Compustat database of company financial statements. Anyone who has ever worked with company-level tax data knows the frustrations in trying to develop historical measures. For individual companies, the effective tax rate can swing wildly from year-to-year, and during major crises, many companies report negative pre-tax income, which makes the tax rate impossible to interpret. For example, on the surface of things, a negative tax rate may sound like a good thing if it is a product of a positive denominator of profits and a negative numerator of taxes paid, but not if it is the product of a negative denominator and a positive numerator.

One way around these problems is to estimate the aggregate effective tax rate. Instead of calculating the effective tax rate for each individual company and then averaging those individual rates, an aggregate tax rate sums together all companies’ income taxes during a certain time period and divides them by all companies’ pre-tax income during that same period. To smooth out the effects of the business cycle, we can sum together the data in the numerator and the denominator over three-, five- or even ten-year periods.

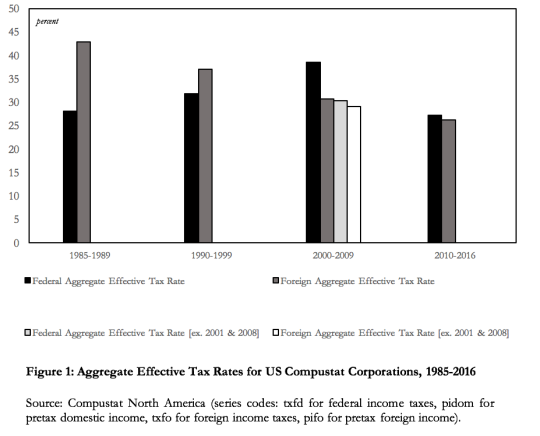

Figure 1 shows the aggregate federal and the aggregate foreign effective tax rates for all US corporations in the Compustat database that report these data items. Specifically, the figure shows the aggregate sum of federal and foreign taxes for a specific period divided by the aggregate sum of domestic and foreign pre-tax income for that same period. The periods are divided by decades, except in the case of 1985–1989 (where earlier data are unavailable) and 2010–2016.

What does Figure 1 tell us? In the 1980s, the aggregate federal effective tax rate of 28 percent for US companies was much lower than the aggregate foreign effective tax rate of 42 percent. Since then, the aggregate foreign effective tax rate of US companies has steadily declined. It stands at 26 percent for the most recent period. Even when we remove the crisis years of 2001 and 2008, the decline in the foreign rate remains. The pattern of federal taxation is harder to discern. The federal rate moves up and down over time and appears to be heavily influenced by the business cycle, rising and then falling in the most recent period. But when we remove the crisis years of 2001 and 2008, during which pre-tax domestic income collapsed, the discrepancy between the foreign and effective rates during the 2000–2009 period disappears.

The data in Figure 1 point toward a long-term global convergence in corporate tax rates. Today the tax rate that US companies pay on their domestic and foreign income is almost identical at 27 and 26 percent, respectively. If anything, what this tells us is that the rest of the world has been engaged in a decades-long process of catching up with the United States’ low corporate tax rate regime. As modest as this empirical exercise may be, it does give good reason to question the Trump administration’s rationale for corporate tax cuts. A long-term view demonstrates that US federal tax policy has not, as the administration would have us believe, hampered the competitiveness of US corporations.

Looking to the future, what are the potential consequences of the recently enacted US corporate tax cuts? Here, I would suggest, there is cause for concern. If the past is a window into the future, then the US cuts may well engender a downward spiral, as other countries slash their rates in response, thereby prompting another process of convergence at even lower rates across the world in the future. The massive political win that corporate tax cuts signal for US big business may in fact represent a massive win for big business on a global scale.