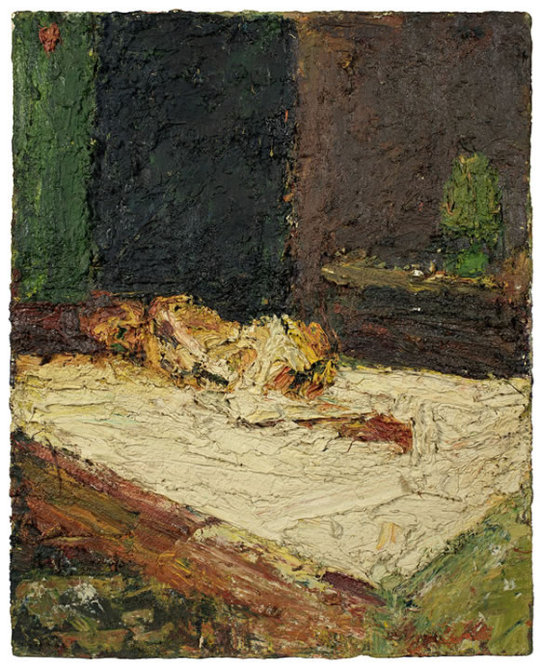

‘Nude on Bed’ (1959) – Frank Auerbach

Reading outside of one’s field can be bad for the academic career, but great for the soul. For years now, at least since watching Adam Curtis’s documentary Century of the Self over a decade ago, I have been meaning to delve into the work of Sigmund Freud. Being on strike for the USS pensions dispute, I haven’t had much motivation to do research-related reading. And so this week seemed like an opportune time to finally read Civilization and Its Discontents.

What struck me most about this book is its accessibility. This has partly to do with Freud’s lucid prose, and partly to do with the fact that so many of his concepts have seeped into popular culture. The “ego/id/superego,” the “narcissism of small differences,” are all familiar, even to someone (like me) only vaguely acquainted with Freud’s work.

What also struck me was the way that this particular book speaks to some of the foundational themes of philosophy and political theory. Considered to be the father of psychoanalysis, much of the popular discussion of Freud focuses on his ideas about the individual. Yet, at least in Civilization and Its Discontents, Freud develops what might best be described as a social contract theory with a psychoanalytic twist. In what follows, I summarize the most important points I took from the book.

As the title of the book suggests, Freud addresses the question of why civilization seems to make us so unhappy. After all, civilized society provides us with many of the things we value, including beauty, order, and cleanliness. It fills us with a sense of security. And it allows us to forge close bonds with other humans that extend from the family, to the tribe, to the nation-state.

According to Freud, the reason why civilization fills us with discontent is because it restricts our individual freedom. In particular, civilization forces us to give up our natural aggressiveness. To be functioning members of society, we have to repress our instinctual drives, including the ever-important sexual drives. Through the process of sublimation, the superego emerges as a mechanism to regulate our individual behaviour, and at the societal level, the super ego emerges through a system of ethics, the most important of which has been religious doctrine.

But these ethical systems place unreasonable demands on the individual, and these unreasonable demands fill us with an unending sense of guilt. Freud makes constant reference to the belief in Christianity that one must “love thy neighbour,” and in fact, even “love thy enemy.” For Freud adherence to these beliefs forces us to inflate the concept of love in a way that, ultimately, devalues it. These beliefs also go against our naturally aggressive nature. He invokes the Latin proverb Homo homini lupus (”man is wolf to man”), to make this point.

At the heart of the development of civilization is a struggle between two conflicting drives: Eros and the ‘death-drive.’ The former is a force libidinally binding humanity together into a great unit, the latter is a destructive force seeking return to a primordial inorganic state. Religion, a “lullaby about heaven” is constructed to deny the struggle between these two forces.

Freud’s pessimistic view of human nature leads him to a critique of Marxism. He argues that Marxists hold a naive conception of human nature: this nature is corrupted by private property, and so getting rid of private property will restore our inherent goodness. But Freud argues that abolishing private property will not eliminate aggressive sexual traits that existed long before the institution of private property. In the future, I want to find out how Marxists have responded to Freud’s critique. Perhaps it has been addressed in Erich Fromm’s Marx’s Concept of Man and/or Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization?