Joseph Baines and Sandy Brian Hager

Across the major economies, concerns have been rising over mounting corporate debt. In the United States, against the backdrop of decades-long access to cheap money, non-financial corporations have seen their debt burdens more than double from $3.2 trillion in 2007 to $6.6 trillion in 2019.

According to some prominent accounts, corporate debt is a giant bubble, and when it pops it could act as a spark that sets off the next global crisis much like subprime mortgages did back in 2007-2008. In this perilous situation, a sudden shock to the system could set off a wave of corporate defaults, putting the entire global financial system at risk of another meltdown.

Now we’re facing that sudden shock. A major one. It goes by the name of COVID-19.

With the spread of the coronavirus (COVID-19), now classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization, the global economy has been thrown into disarray. Supply chains and travel networks have been severely disrupted, stock markets have tanked, and a recession now seems almost inevitable. Even the US Treasuries market, normally a bastion of safety during periods of market turmoil, has become extremely volatile.

The situation is fluid and uncertain, making any projections about even short-term consequences tenuous at best. But given the gravity of the situation, it is nevertheless worth asking: Does the arrival of COVID-19 mean that the day of reckoning for overstretched corporate borrowers is at hand?

Over the past year, we have been conducting research that maps out the structure of indebtedness for nonfinancial corporations in the United States listed on the stock market. Our findings suggest that the pundits are right to be concerned about increasing corporate leverage. But we have to be careful in specifying which corporations are most susceptible to default. In breaking down debt levels for corporations of different sizes, our analysis yields some stunning results.

What we find is that small and medium-sized corporations face the most significant debt burdens, making them especially vulnerable to a market downturn. Meanwhile firms in the uppermost echelon appear to be more financially robust than they have been for almost half a century. If COVID-19 is indeed the catalyst for a corporate debt catastrophe, we expect it to hit those at the bottom hardest. The likely result? More market turmoil, concentration, and less investment.

Shareholder Capitalism

Before turning to discuss corporate indebtedness, we ask that the reader to bear with us as we set the scene. Providing some needed background information will allow us to tackle the question of why corporate debt has been rising and why it’s been increasing particularly for small and medium sized firms. The answer, we think, has to do with the dynamics of concentration under shareholder capitalism.

Corporate governance in the US underwent a shift roughly forty years ago. In the post-World War II period, corporations tended to retain their earnings and reinvest them in productive capacity. Since the early 1980s, the predominant strategy has been to maximize shareholder value through downsizing operations and distributing earnings to the owners of company shares.

There’s been plenty of research tracing this shift from ‘retain and reinvest’ to ‘downsize and distribute’ for the US corporate sector. But little has been said about the degree to which corporations of different sizes have embraced the ideology of shareholder value maximization.

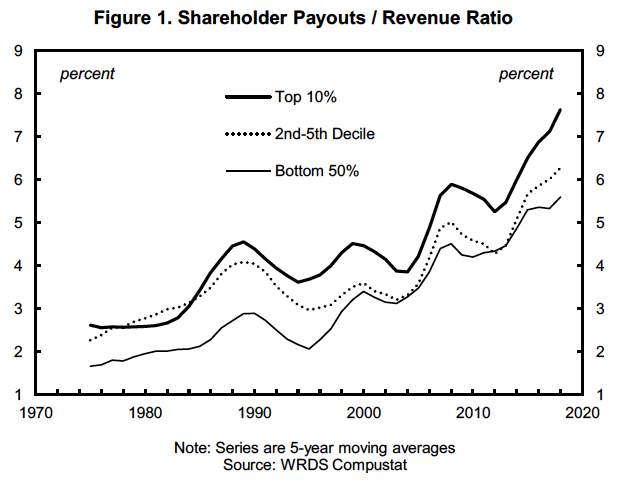

In Figure 1, we tackle the ‘distribute’ side of ‘downsize and distribute’ by examining dividend payments and stock buybacks as a percentage of revenues for US-headquartered nonfinancial corporations that are listed on the stock market. The figure differentiates between the top 10 percent, the second to fifth decile, and the bottom 50 percent of corporations ranked by their total revenues.

We see that the top 10 percent has been more committed to shareholder distributions than firms in the bottom 90 percent. Yet, although large corporations appear to be leading the charge, there has clearly been a secular rise in dividend payments and stock buybacks for corporations of all sizes since the 1970s.

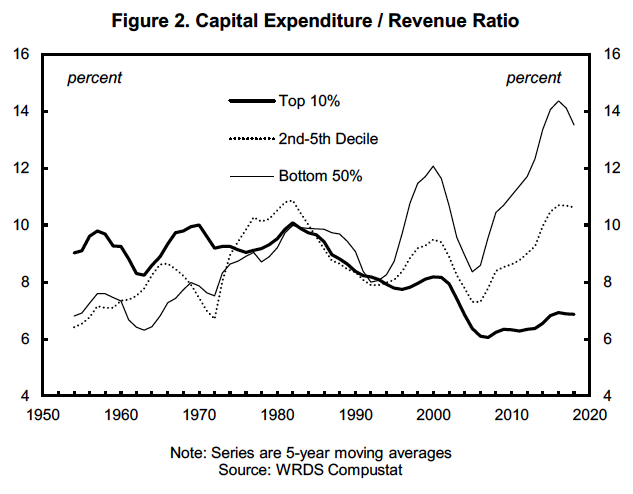

What about the ‘downsizing’ side of ‘downsize and distribute’? In Figure 2 we examine capital expenditures as a percentage of revenues as a proxy for the degree of downsizing. We see that firms in the top decile have clearly downsized since the 1980s. But what’s fascinating is that the capital expenditure commitment of firms in the bottom 90 percent has actually been on the rise.

In compiling these data, we were puzzled. All corporations are committed to distributing earnings to shareholders, but only the largest corporations have embraced the downsizing side of the ideology of shareholder value maximization. The top 10 percent treats shareholder distributions and capital expenditures as a trade-off, but smaller corporations don’t. Why is this the case?

Zombie Firms

No matter what their relative size, our data suggest that all firms are subject to competitive pressures from financial markets. This means that even firms in the top decile face pressures from financial markets to maintain decent returns for their shareholders. But because firms in the top decile tend to dominate the sectors in which they operate, they don’t have to engage in much capital expenditure to maintain supremacy. Firms in the bottom 90 percent, however, not only have to establish themselves through large-scale capital investment, they also have to appease shareholders who are continually demanding higher returns on their investments.

This puts smaller firms in a very precarious position. And what we argue is that the dynamics of shareholder capitalism have pushed the firms in the lower echelons of the US corporate hierarchy into a state of financial distress.

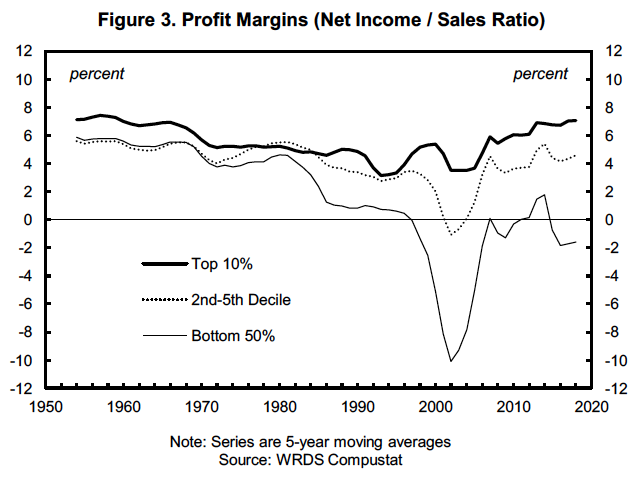

Acute signs of this distress can be seen in Figure 3 on the profitability of corporations within our three categories. The chart highlights the polarization of profitability among US corporations over the last seven decades as measured by profit margins: the amount of net profits in sales. The top 10 percent has enjoyed a general rise in profit margins since the mid-1990s, while the profit margins of firms in the bottom half were mostly in negative territory in the same period.

Broadly speaking, the bottom half of the distribution includes many zombie firms that have received much attention in the financial press. How do these zombies at the bottom of the hierarchy survive? Our research suggests that instead of feasting on human brains, they’re feasting on debt.

The Debt Feast

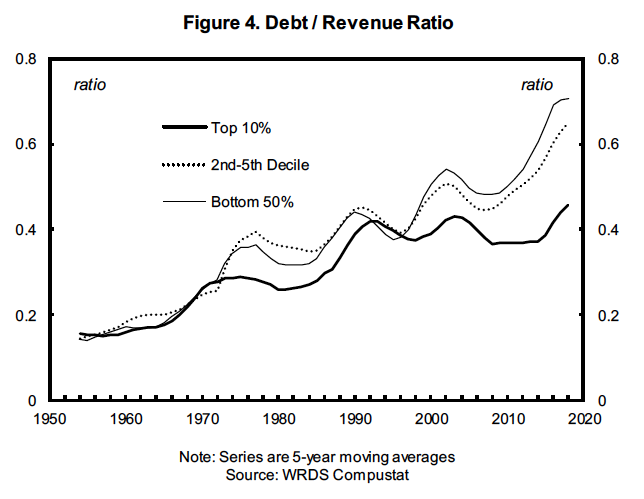

Figure 4 shows debt-to-revenue ratios for our three categories of firms. We see a secular rise in leverage for all three groups since the 1950s. But what is also clear is that the debt burden has been unevenly distributed. The leverage of the top 10 percent has been more or less flat since the early 1990s, while the debt burdens of firms in the bottom half, as well as the second to fifth decile, have risen steeply over that same period.

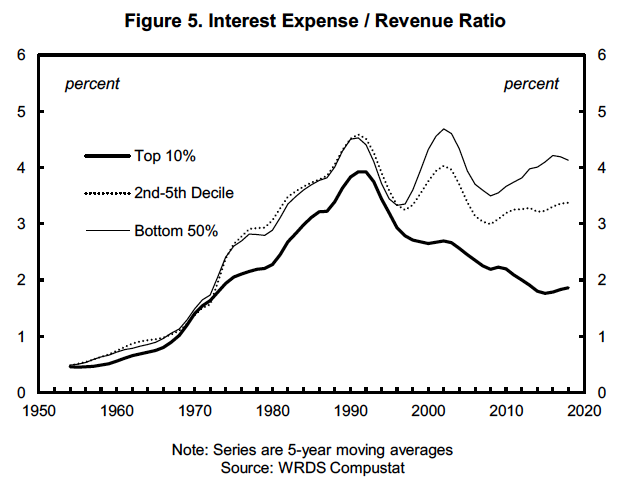

In assessing the sustainability of these debt burdens, we also have to take into account debt servicing costs. We do this in Figure 5, which tracks interest expenses as a percentage of revenues for all three categories of firms. One thing that stands out is the sharp fall in debt servicing costs for the top 10 percent since the peak in the early 1990s. Even though they’re taking on larger debt burdens, firms in the second to fifth decile have seen their debt servicing costs fall. And even though the bottom 50 percent has seen the most dramatic rise in their debt burden since the 1990s, its debt servicing costs have held more or less steady, though it’s worth noting that these costs are nearly twice as high as for the top ten percent.

Viewed in isolation, the data on debt servicing costs might make us optimistic about the sustainability of corporate debt burdens. Yet all other signs point to acute distress for firms at the bottom. The only thing that appears to be keeping many of these smaller companies afloat is cheap money, with ultra-low interest rates facilitating rising indebtedness. We’re in dangerous waters. If creditors are spooked, and debt servicing costs rise, the bottom could quite literally fall out.

Why Does it Matter?

Finally, we come to the question of why we should care about this. So what if COVID-19 manages to kill off a bunch of smaller firms, especially if the bottom 50 percent includes a bunch of zombies? We think there are three good reasons to be worried about the situation we’ve outlined here.

First, as hinted at earlier, a wave of defaults by smaller firms could send shockwaves through already-jittery financial markets, providing a catalyst for a wider meltdown. Second, corporate giants at the top will further consolidate their power, increasing concentration in an already concentrated US corporate sector. This would be an unwelcome development given the mounting evidence regarding the negative impact of concentration on the US economy. And third, as shown in Figure 2, a debt crisis that kills off a significant number of smaller firms would also have a negative impact on capital expenditures. Despite the zombie moniker, the bottom 50 percent has been expanding its productive capacity in recent decades, while the top 10 percent has lagged behind. If smaller companies are allowed to drown in their own debt, we will lose one of the main sources of job creation and innovation.